I teach a course at BGSU called "Imaginative Writing." But what is the imagination? I don't think there's one agreed upon definition. But clearly, long ago humans developed an ability to recognize special, magical moments in life. They developed the ability to describe their exterior world, and to participate in self-knowledge. They learned to describe their inner world.

Somewhere along the line, some designated themselves as transmitters of this magic, of this wisdom. They were the shamans and the artists. Those of us who try to follow in their footsteps benefit from their wisdom.

I've written in earlier entries about how--when my writing is going very well--I feel like I'm traveling into my center, into my true self. And that this center seems connected to something divine, though I don't really understand the essence of that divinity.

This I do know: The return to that experience of mystery is one of the things that keeps me coming back to the writing act.

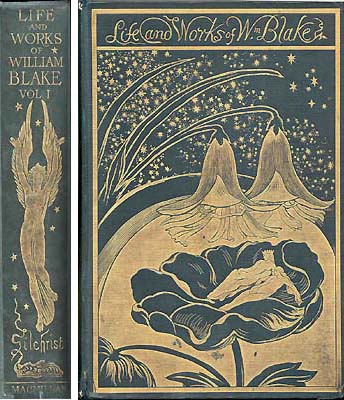

I'm not alone in the experience of the divine. William Blake, my inexhaustible source of inspiration, wrote:

I rest not from my great task!

To open the Eternal Worlds, to open the immortal Eyes

Of Man inwards into the Worlds of Thought, into Eternity

Ever expanding in the Bosom of God, the Human Imagination

Colridge also felt the imagination is the "organ of the divine."

Colridge thought that the imagination is "the highest faculty that synthesizes experience into imagery. It perceives shape or form and order, using different, even opposite, elements of feeling, vision, and thought to achieve a unified whole. In other words, it fuses and assimilates the daily experiences into a larger unity." (I. M. Oderberg)

I like that thought, that it is the artist's task to FUSE AND ASSIMILATE DAILY EXPERIENCES INTO A LARGER UNITY. This is also why it is so important to read the work of other writers, and to read widely. The work of other writers will become part of your own consciousness. You will have a deep well to draw from when it's time to do your own work.

Shelley thought that the imagination helped us to access the "real" world.

(Oh! How I love this: Shelley's notion of what the "real" world is!)...

He thought we only experience the "real" world during moments when we feel illuminated, when we become aware of "the heart of things." In other words, when we sense the presence of the eternal. (Think about this the next time you hear someone snidely suggest: "Get real!"--thinking of Shelley will give you a wonderful, secret thrill!)

Blake thought humans were fallen souls from heaven that needed to get back to their original state as spiritual beings. He thought it was the job of the artist to help humans get back to that state of existence.

Blake wrote in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, "If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern."

Blake thought the imagination to be the creative soul of the universe, life itself "a ceaseless crossing of thresholds, an endless being through becoming...endless...endless time...no beginning, no end..."

I think the imagination is also our way to recognize possibility. This "ceaseless crossing of thresholds" causes a change, a growth. It's like the idea of the Tibetan Buddhist who sees in the heart the "jewel in the lotus." As we cross the thresholds, the jewel becomes more and more polished until our full inner potentiality is reached.

I think when I write, I'm polishing the jewel. It is a never ending process. So it's the journey wherein we glimpse the eternal. On the whole, we will often feel ragged and unfinished. But, oh, we will also have those moments when we see through the narrow chinks of our cavern. We live for those. We live for those!

I think the artist's task is to try to portray that journey, and when we portray it, we take the participants of our art along with us; or, better, set them out on their own journey. To me, the poem by Dag Hammarskjold describes the creative act perfectly. We leave the mediocre, "everyday" world and enter the unknown land of the imagination. We don't know what we will discover; we often don't even know what our goal is. But we vaguely know what we seek--that clear, pure note of "truth":

Thus It Was

by Dag Hammarskjold

I am being driven forward

Into an unknown land.

The pass grows steeper,

The air colder and sharper,

A wind from my unknown goal

Stirs the strings

Of expectation.

Still the question:

Shall I ever get there?

There where life resounds,

A clear pure note

In the silence.

To get there, I believe we have to work hard on making ourselves the kind of indivividuals who can perceive this "truth." We can't perceive it unless it exists within ourselves. That, for me, is where writing and the spiritual life merge:

You cannot see beauty outside unless you have beauty within you. You cannot understand beauty unless you yourself are beautiful inside. You cannot understand harmony unless you yourself in your inner parts are harmony. All things of value are within yourself, and the outside world merely offers you the stimulus, the stimulation, of and to the exercise of the understanding faculty within you. -- G. de Purucker