Listening is a magnetic and strange thing, a creative force. When people really listen to each other in a quiet, fascinated attention, the creative fountain inside each of us begins to spring and cast up new thoughts and unexpected wisdom.

— Brenda Ueland quoted in Finding What You Didn't Lose by John Fox

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I think sometimes we forget that writing and reading are a form of listening.

When we write, we listen to our inner truths and we listen to the big questions about life. This doesn't mean think about creating "great literature." That is the human ego and you can never live up to that standard anyway.

Instead of listening to the human ego, I think you have to to listen to life. I have written a great deal about how important writing is to me. But Ueland said the great Russian writers were great because life was more important to them than literature. This is true and something I often need to be reminded of.

And Ueland also said, "If good ideas do not come at once, do not be troubled at all. Wait for them. Put down the little ideas however insignificant they are. But do not feel, any more, guilty about idleness and solitude." When you are in your quiet time, go to the bottom of your "self" and listen. Out of the idleness will come the truth, which will not be a fancy plot. As John Gardner says, plot is just a device used to help your characters reveal themselves.

I believe Sandy, who keeps the journal "Mental Jewelry," is onto something when she says of that "somewhere" our writing must go: "And if in journaling, could that be self? An internal 'somewhere?'"

In writing, we most certainly must listen and speak to that internal "somewhere."

Then, after listening, we write the thing we would most like to read ourselves; in this way--and only this way--we are truly listening to the needs of our readers.

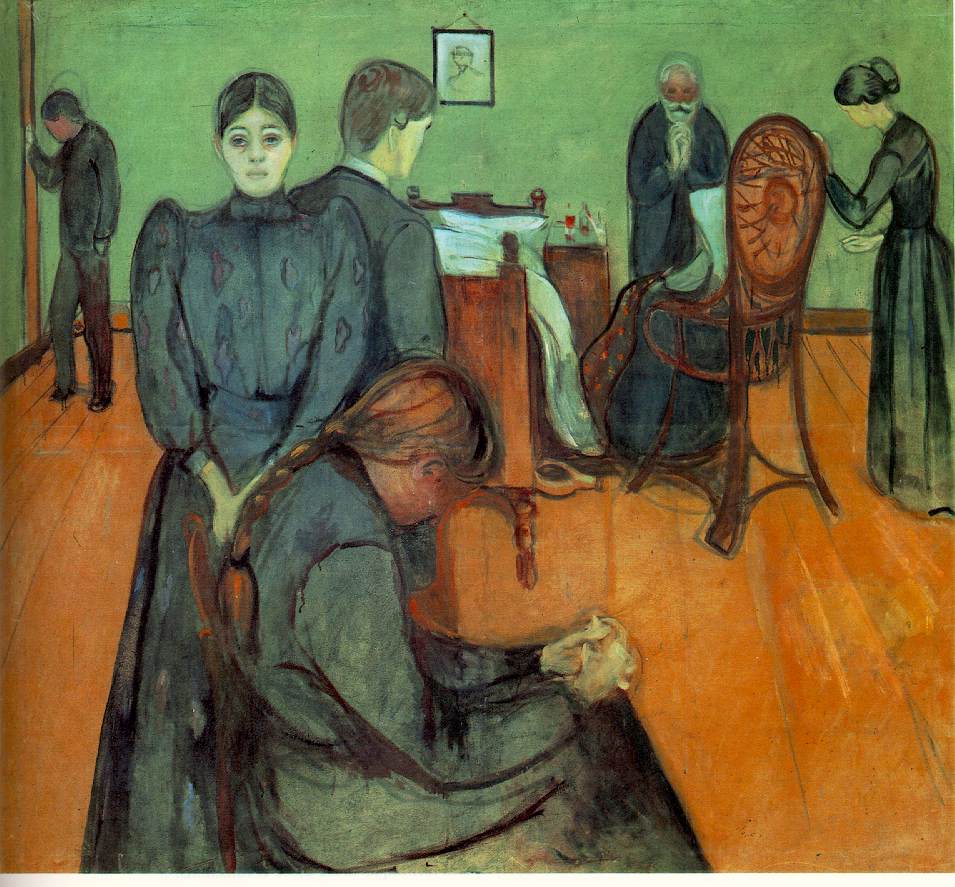

Moreover, when we read, we are listening to the soul (personality) of the writer. We experiencing that writer's imagination clearly. We experience the source of the words as being "an actual and living person," according to Ueland. She also said:

"The personality behind the writing is so important. This is what I call the Third Dimension. On the paper there are all the neatly written words and sentences. It may be completely objective, with 'I' not written there once. But behind the words and sentences, there is a deep, important, moving thing--the personality of the writer. And whatever that personality is, it will shine through the writing and make it noble or great, or touching or cold or niggardly or supercilious or whatever the writer is."

To experience that Third Dimension as we read, we listen.

To know what to write, we listen.

We cannot speak with authority until we listen.

All artists are great listeners!